- Market services

-

Compliance audits & reviews

Our audit team undertakes the complete range of audits required of Australian accounting laws to help you to help you meet obligations or fulfil best practice procedures.

-

Audit quality

We are fiercely dedicated to quality, use proven and globally tested audit methodologies, and invest in technology and innovation.

-

Financial reporting advisory

Our financial reporting advisory team helps you understand changes in accounting standards, develop strategies and communicate with your stakeholders.

-

Audit advisory

Grant Thornton’s audit advisory team works alongside our clients, providing a full range of reviews and audits required of your business.

-

Digital assurance

We capture actionable, quality insights from data within your financial reporting and auditing processes.

-

Corporate tax & advisory

We provide comprehensive corporate tax and advisory service across the full spectrum of the corporate tax process.

-

Private business tax & advisory

We work with private businesses and their leaders on all their business tax and advisory needs.

-

Tax compliance

We work alongside clients to manage all tax compliance needs and identify potential compliance or tax risk issues.

-

Employment tax

We help clients understand and address their employment tax obligations to ensure compliance and optimal tax positioning for their business and employees.

-

International tax

We understand what it means to manage tax issues across multiple jurisdictions, and create effective strategies to address complex challenges.

-

GST, stamp duty & indirect tax

Our deep technical knowledge and practical experience means we can help you manage and minimise the impact of GST and indirect tax, like stamp duty.

-

Tax law

Our team – which includes tax lawyers – helps you understand and implement regulatory requirements for your business.

-

Innovation Incentives

Our national team has extensive experience navigating all aspects of the government grants and research and development tax incentives.

-

Transfer pricing

Transfer pricing is one of the most challenging tax issues. We help clients with all their transfer pricing requirements.

-

Tax digital consulting

We analyse high-volume and unstructured data from multiple sources from our clients to give them actionable insights for complex business problems.

-

Corporate simplification

We provide corporate simplification and managed wind-down advice to help streamline and further improve your business.

-

Superannuation and SMSF

Increasingly, Australians are seeing the benefits, advantages and flexibility of taking control of their own superannuation and retirement planning.

-

Payroll consulting & Award compliance

Many organisations are grappling with a myriad of employee agreements and obligations, resulting in a wide variety of payments to their people.

-

Cyber resilience

The spectrum of cyber risks and threats is now so significant that simply addressing cybersecurity on its own isn’t enough.

-

Internal audit

We provide independent oversight and review of your organisation's control environments to manage key risks, inform good decision-making and improve performance.

-

Financial crime

Our team helps clients navigate and meet their obligations to mitigate crime as well as develop and implement their risk management strategies.

-

Consumer Data Right

Consumer Data Right (CDR) aims to provide Australians with more control over how their data is used and disclosed.

-

Risk management

We enable our clients to achieve their strategic objectives, fulfil their purpose and live their values supported by effective and appropriate risk management.

-

Controls assurance

In Australia, as with other developed economies, regulatory and market expectations regarding corporate transparency continue to increase.

-

Governance

Through fit for purpose governance we enable our clients to make the appropriate decisions on a timely basis.

-

Regulatory compliance

We enable our clients to navigate and meet their regulatory and compliance obligations.

-

Forensic accounting and dispute advisory

Our team advises at all stages of a litigation dispute, taking an independent view while gathering and reviewing evidence and contributing to expert reports.

-

Investigations

Our licensed forensic investigators with domestic and international experience deliver high quality results in the jurisdictions in which you operate.

-

Asset tracing investigations

Our team of specialist forensic accountants and investigators have extensive experience in tracing assets and the flow of funds.

-

Mergers and acquisitions

Our mergers and acquisitions specialists guide you through the whole process to get the deal done and lay the groundwork for long-term success.

-

Acquisition search & strategy

We help clients identify, finance, perform due diligence and execute acquisitions to maximise the growth opportunities of your business.

-

Selling a business

Our M&A team works with clients to achieve a full or partial sale of their business, to ensure achievement of strategic ambitions and optimal outcomes for stakeholders.

-

Operational deal services

Our operational deal services team helps to ensure the greatest possible outcome and value is gained through post merger integration or post acquisition integration.

-

Transaction advisory

Our transaction advisory services support our clients to make informed investment decisions through robust financial due diligence.

-

ESG Due Diligence

Our ESG due diligence process evaluates a company's environmental, social, and governance factors during the pre-investment phase to determine the overall maturity of the entity, manage potential risks, and identify opportunities.

-

Business valuations

We use our expertise and unique and in-depth methodology to undertake business valuations to help clients meet strategic goals.

-

Tax in mergers & acquisition

We provide expert advice for all M&A taxation aspects to ensure you meet all obligations and are optimally positioned.

-

Corporate finance

We provide effective and strategic corporate finance services across all stages of investments and transactions so clients can better manage costs and maximise returns.

-

Debt advisory

We work closely with clients and lenders to provide holistic debt advisory services so you can raise or manage existing debt to meet your strategic goals.

-

Working capital optimisation

Our proven methodology identifies opportunities to improve your processes and optimise working capital, and we work with to implement changes and monitor their effectiveness.

-

Capital markets

Our team has significant experience in capital markets and helps across every phase of the IPO process.

-

Debt and project finance raising

Backed by our experience accessing full range of available funding types, we work with clients to develop and implement capital raising strategies.

-

Private equity

We provide advice in accessing private equity capital.

-

Financial modelling

Our financial modelling advisory team provides strategic, economic, financial and valuation advice for project types and sizes.

-

Payments advisory

We provide merchants-focused payments advice on all aspects of payment processes and technologies.

-

Voluntary administration & DOCA

We help businesses considering or in voluntary administration to achieve best possible outcomes.

-

Corporate insolvency & liquidation

We help clients facing corporate insolvency to undertake the liquidation process to achieve a fair and orderly company wind up.

-

Complex and international insolvency

As corporate finance specialists, Grant Thornton can help you with raising equity, listings, corporate structuring and compliance.

-

Safe Harbour advisory

Our Safe Harbour Advisory helps directors address requirements for Safe Harbour protection and business turnaround.

-

Bankruptcy and personal insolvency

We help clients make informed choices around bankruptcy and personal insolvency to ensure the best personal and stakeholder outcome.

-

Creditor advisory services

Our credit advisory services team works provides clients with credit management assistance and credit advice to recapture otherwise lost value.

-

Small business restructuring process

We provide expert advice and guidance for businesses that may need to enter or are currently in small business restructuring process.

-

Asset tracing investigations

Our team of specialist forensic accountants and investigators have extensive experience in tracing assets and the flow of funds.

-

Independent business reviews

Does your company need a health check? Grant Thornton’s expert team can help you get to the heart of your issues to drive sustainable growth.

-

Commercial performance

We help clients improve commercial performance, profitability and address challenges after internal or external triggers require a major business model shift.

-

Safe Harbour advisory

Our Safe Harbour advisory helps directors address requirements for Safe Harbour protection and business turnaround.

-

Corporate simplification

We provide corporate simplification and managed wind-down advice to help streamline and further improve your business.

-

Director advisory services

We provide strategic director advisory services in times of business distress to help directors navigate issues and protect their company and themselves from liability.

-

Debt advisory

We work closely with clients and lenders to provide holistic debt advisory services so you can raise or manage existing debt to meet your strategic goals.

-

Business planning & strategy

Our clients can access business planning and strategy advice through our value add business strategy sessions.

-

Private business company secretarial services

We provide company secretarial services and expert advice for private businesses on all company secretarial matters.

-

Outsourced accounting services

We act as a third-party partner to international businesses looking to invest in Australia on your day-to-day finance and accounting needs.

-

Superannuation and SMSF

We provide SMSF advisory services across all aspects of superannuation and associated tax laws to help you protect and grow your wealth.

-

Management reporting

We help you build comprehensive management reporting so that you have key insights as your business grows and changes.

-

Financial reporting

We help with all financial reporting needs, including set up, scaling up, spotting issues and improving efficiency.

-

Forecasting & budgeting

We help you build and maintain a business forecasting and budgeting model for ongoing insights about your business.

-

ATO audit support

Our team of experts provide ATO audit support across the whole process to ensure ATO requirements are met.

-

Family business consulting

Our family business consulting team works with family businesses on running their businesses for continued future success.

-

Private business taxation and structuring

We help private business leaders efficiently structure their organisation for optimal operation and tax compliance.

-

Outsourced CFO services

Our outsourced CFO services provide a full suite of CFO, tax and finance services and advice to help clients manage risk, optimise operations and grow.

-

Sustainability reporting

Following the introduction of mandatory sustainability reporting requirements in Australia, organisations will need to understand if they are required to report, the disclosure requirements, and if they have the skill set and available data to comply. We can guide organisations through the reporting process end-to-end, from climate-related risks and opportunities identification through to reporting support.

-

Sustainability advisory

With the ESG and sustainability landscape continuing to evolve, we are focused on helping your business to understand how to shape your sustainability strategy. When designing a sustainability strategy, it’s important to take into consideration your sustainability-related risks and opportunities, relevant standards and frameworks such as the SBTi, and your broader business needs.

-

Sustainability assurance

The sustainability reporting regulations which have come into force in Australia include assurance requirements which are being phased in over several years. Australia is also the first jurisdiction internationally to adopt the new assurance standard. Whether you are seeking voluntary assurance or meeting your compliance obligations, our sustainability assurance team combines technical expertise and industry insights to provide quality and efficiency in the assurance process.

-

ESG due diligence

As ESG and Sustainability-related considerations are becoming pivotal for Australian dealmakers, it is important for investors to feel confident in assessing transactions through an ESG lens. The due diligence process evaluates a company's material environmental, social, and governance topics during the pre-investment phase, flagging risks and identifying opportunities for added value.

-

Management consulting

Our management consulting services team helps you to plan and implement the right strategy to deliver sustainable growth.

-

Financial consulting

We provide financial consulting services to keep your business running so you focus on your clients and reaching strategic goals.

-

China practice

The investment opportunities between Australia and China are well established yet, in recent years, have also diversified.

-

Japan practice

The trading partnership between Japan and Australia is long-standing and increasingly important to both countries’ economies.

-

India practice

It’s an exciting time for Indian and Australian businesses looking to each jurisdiction as part of their growth ambitions.

-

Singapore practice

Our Singapore Practice works alongside Singaporean companies to achieve growth through investment and market expansion into Australia.

-

Vietnam practice

Investment and business opportunities in Vietnam are expanding rapidly, driven by new markets, diverse industries, and Vietnam's growing role in export manufacturing, foreign investment, and strong domestic demand.

-

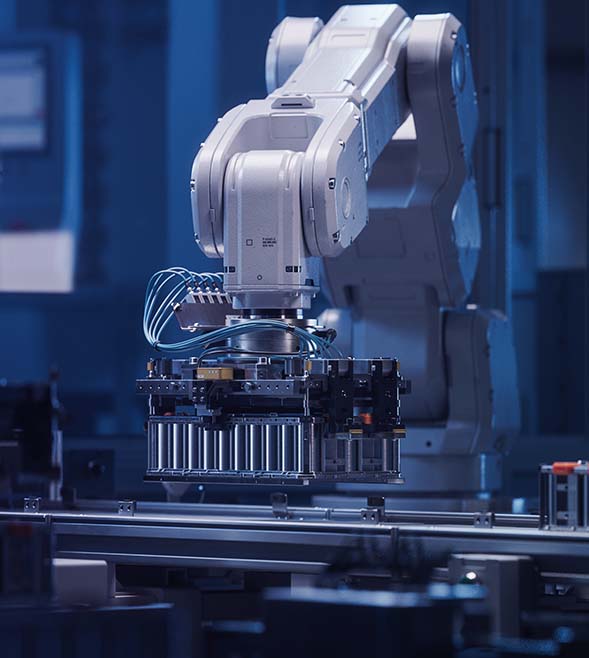

Podcast Finding the right fit in the evolving world of supply chain solutionsIn this episode of Beyond the Numbers with Grant Thornton, Management Consulting Partner, Richard Bycroft, and Director, Primo Danieletto, discuss automation in supply chains, triggers for reviewing an organisation’s current model and the ROI businesses can see from implementation.

Podcast Finding the right fit in the evolving world of supply chain solutionsIn this episode of Beyond the Numbers with Grant Thornton, Management Consulting Partner, Richard Bycroft, and Director, Primo Danieletto, discuss automation in supply chains, triggers for reviewing an organisation’s current model and the ROI businesses can see from implementation. -

Client Alert Tax treatment of the proceeds on the sale of landThe Federal Court decision in Morton v Commissioner of Taxation [2025] FCA 336 (“the Morton case”) provides key guidance on the tax treatment of proceeds derived from land development arrangements. This is particularly relevant to landowners considering development partnerships with third-party developers.

Client Alert Tax treatment of the proceeds on the sale of landThe Federal Court decision in Morton v Commissioner of Taxation [2025] FCA 336 (“the Morton case”) provides key guidance on the tax treatment of proceeds derived from land development arrangements. This is particularly relevant to landowners considering development partnerships with third-party developers. -

Client Alert ATO releases new GST guidance on prepared mealsThe ATO’s GSTD 2025/1 clarifies the GST treatment of prepared meals following the Simplot case. Learn how the new four-step test and transitional compliance approach affect food suppliers.

Client Alert ATO releases new GST guidance on prepared mealsThe ATO’s GSTD 2025/1 clarifies the GST treatment of prepared meals following the Simplot case. Learn how the new four-step test and transitional compliance approach affect food suppliers. -

Client Alert Wine not? Primary production land tax exemption no longer on the vineFor wine producers and vineyard owners, the recent New South Wales Civil and Administrative Tribunal decision in Zonadi Holdings Pty Ltd ATF Wombat Investment Trust v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue [2025] NSWCATAD 84 may spell trouble for their current primary production land tax exemptions.

Client Alert Wine not? Primary production land tax exemption no longer on the vineFor wine producers and vineyard owners, the recent New South Wales Civil and Administrative Tribunal decision in Zonadi Holdings Pty Ltd ATF Wombat Investment Trust v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue [2025] NSWCATAD 84 may spell trouble for their current primary production land tax exemptions.

-

Report Balancing risk and opportunity in mining contracting reportMining contractors are operating in an increasingly complex and competitive Australian mining sector. With shifting commodity markets, cost pressures, and evolving contract models, understanding contractor performance, financial strength, and growth opportunities is more important than ever.

Report Balancing risk and opportunity in mining contracting reportMining contractors are operating in an increasingly complex and competitive Australian mining sector. With shifting commodity markets, cost pressures, and evolving contract models, understanding contractor performance, financial strength, and growth opportunities is more important than ever. -

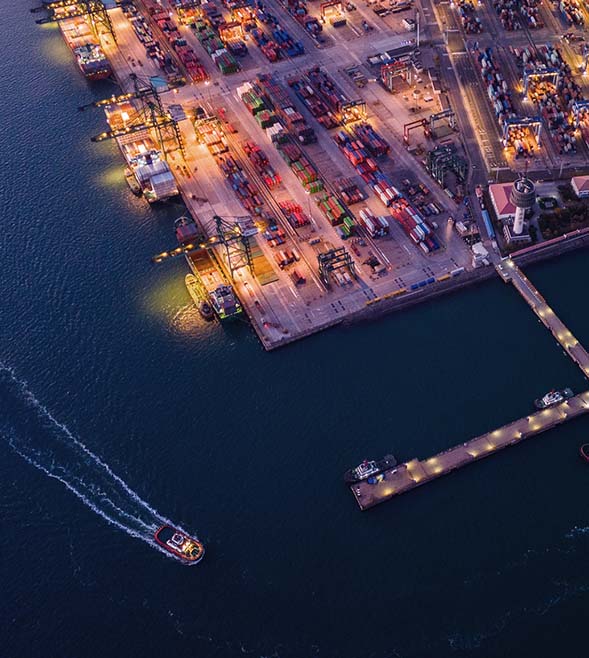

Insight Impact of retaliatory tariffs on Australian and New Zealand exportersAs of April 9, 2025, a minimum universal tariff of 10 per cent has been applied to all imported goods into the United States, while certain countries face higher reciprocal tariffs based on their US trade deficit.

Insight Impact of retaliatory tariffs on Australian and New Zealand exportersAs of April 9, 2025, a minimum universal tariff of 10 per cent has been applied to all imported goods into the United States, while certain countries face higher reciprocal tariffs based on their US trade deficit. -

Insight Critical Minerals and Hydrogen Production Tax Incentives – legislation passedThe Australian Parliament recently passed legislation to introduce two significant tax incentives aimed at bolstering Australia’s critical minerals and hydrogen production sectors. The incentives form a significant part of the Government’s ’Future Made in Australia‘ policy.

Insight Critical Minerals and Hydrogen Production Tax Incentives – legislation passedThe Australian Parliament recently passed legislation to introduce two significant tax incentives aimed at bolstering Australia’s critical minerals and hydrogen production sectors. The incentives form a significant part of the Government’s ’Future Made in Australia‘ policy. -

Client Alert Unlock 2025: government grants updateIf government grants are part of your 2025 strategy, take note of the available quarter one funding opportunities. With increasing inflationary pressures, government grants can be an essential alternative funding source for businesses with critical investment projects.

Client Alert Unlock 2025: government grants updateIf government grants are part of your 2025 strategy, take note of the available quarter one funding opportunities. With increasing inflationary pressures, government grants can be an essential alternative funding source for businesses with critical investment projects.

-

Insight Lessons from AusNet’s restructureThe Full Federal Court has handed down its decision in AusNet Services Limited v Commissioner of Taxation. AusNet argued that its 2015 restructure did not qualify for rollover relief under Division 615, despite that it earlier said it did. This case serves as a reminder that once a tax election is made, it is very difficult to unwind. Careful planning and forecasting are critical.

Insight Lessons from AusNet’s restructureThe Full Federal Court has handed down its decision in AusNet Services Limited v Commissioner of Taxation. AusNet argued that its 2015 restructure did not qualify for rollover relief under Division 615, despite that it earlier said it did. This case serves as a reminder that once a tax election is made, it is very difficult to unwind. Careful planning and forecasting are critical. -

Insight ATO final taxation ruling – TR 2025/2: Third Party Debt Test (TPDT)Australia’s new thin capitalisation rules significantly impact businesses with foreign ownership or offshore operations. If your business has debt deductions (such as interest deductions and borrowing costs) of more than A$2m, tax deductions could be denied under the primary ‘earnings tests’ (particularly if your EBITDA is low or negative due to early-stage losses, especially common in sectors like infrastructure and technology). To manage the above risk, the legislation offers an alternative test: the Third Party Debt Test (TPDT).

Insight ATO final taxation ruling – TR 2025/2: Third Party Debt Test (TPDT)Australia’s new thin capitalisation rules significantly impact businesses with foreign ownership or offshore operations. If your business has debt deductions (such as interest deductions and borrowing costs) of more than A$2m, tax deductions could be denied under the primary ‘earnings tests’ (particularly if your EBITDA is low or negative due to early-stage losses, especially common in sectors like infrastructure and technology). To manage the above risk, the legislation offers an alternative test: the Third Party Debt Test (TPDT). -

Insight What the Australian Clinical Labs privacy case means for cyber governance and M&A riskThe Federal Court’s $5.8M ACL decision signals a new era for privacy, cybersecurity, and governance in Australia. It reinforces that privacy and cyber obligations start Day 1 of any acquisition, governance failures will be scrutinised, and accountability cannot be outsourced. Boards must ensure robust oversight, deep cyber due diligence, and forensic incident response. With OAIC escalating regulatory enforcement, organisations face heightened legal, financial, and reputational risks.

Insight What the Australian Clinical Labs privacy case means for cyber governance and M&A riskThe Federal Court’s $5.8M ACL decision signals a new era for privacy, cybersecurity, and governance in Australia. It reinforces that privacy and cyber obligations start Day 1 of any acquisition, governance failures will be scrutinised, and accountability cannot be outsourced. Boards must ensure robust oversight, deep cyber due diligence, and forensic incident response. With OAIC escalating regulatory enforcement, organisations face heightened legal, financial, and reputational risks. -

Insight APRA clarifies governance prudential standards changesIn June this year, APRA published its eight proposed changes to its governance prudential standards. We have summarised APRA’s updated/clarified position and provided guidance on some steps that boards should be doing to prepare for the revised standards.

Insight APRA clarifies governance prudential standards changesIn June this year, APRA published its eight proposed changes to its governance prudential standards. We have summarised APRA’s updated/clarified position and provided guidance on some steps that boards should be doing to prepare for the revised standards.

-

Insight What the Aged Care Act 2024 means for providersThe Aged Care Act 2024 has been in place for a month. Touted as a ‘once in a generation change’ to improve protections for consumers, it also seeks to stimulate investment in residential care services and improve care in the home with the new Support at Home Program.

Insight What the Aged Care Act 2024 means for providersThe Aged Care Act 2024 has been in place for a month. Touted as a ‘once in a generation change’ to improve protections for consumers, it also seeks to stimulate investment in residential care services and improve care in the home with the new Support at Home Program. -

Insight What the Australian Clinical Labs privacy case means for cyber governance and M&A riskThe Federal Court’s $5.8M ACL decision signals a new era for privacy, cybersecurity, and governance in Australia. It reinforces that privacy and cyber obligations start Day 1 of any acquisition, governance failures will be scrutinised, and accountability cannot be outsourced. Boards must ensure robust oversight, deep cyber due diligence, and forensic incident response. With OAIC escalating regulatory enforcement, organisations face heightened legal, financial, and reputational risks.

Insight What the Australian Clinical Labs privacy case means for cyber governance and M&A riskThe Federal Court’s $5.8M ACL decision signals a new era for privacy, cybersecurity, and governance in Australia. It reinforces that privacy and cyber obligations start Day 1 of any acquisition, governance failures will be scrutinised, and accountability cannot be outsourced. Boards must ensure robust oversight, deep cyber due diligence, and forensic incident response. With OAIC escalating regulatory enforcement, organisations face heightened legal, financial, and reputational risks. -

Insight Prospects for the banking sector in health and aged careThe health and aged care industry in Australia is complex and there are a range of challenges and opportunities for the banking sector which can be explored in relation to its various sub-sectors.

Insight Prospects for the banking sector in health and aged careThe health and aged care industry in Australia is complex and there are a range of challenges and opportunities for the banking sector which can be explored in relation to its various sub-sectors. -

Report Considerations for the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission’s proposed Financial StandardsExplore recommendations to improve Aged Care Financial Standards and support provider stability.

Report Considerations for the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission’s proposed Financial StandardsExplore recommendations to improve Aged Care Financial Standards and support provider stability.

-

Insight Unlocking the benefits of Australian Trusted Trader accreditationUnlock ATT accreditation to boost trade compliance, speed, and global market access.

Insight Unlocking the benefits of Australian Trusted Trader accreditationUnlock ATT accreditation to boost trade compliance, speed, and global market access. -

Podcast Finding the right fit in the evolving world of supply chain solutionsIn this episode of Beyond the Numbers with Grant Thornton, Management Consulting Partner, Richard Bycroft, and Director, Primo Danieletto, discuss automation in supply chains, triggers for reviewing an organisation’s current model and the ROI businesses can see from implementation.

Podcast Finding the right fit in the evolving world of supply chain solutionsIn this episode of Beyond the Numbers with Grant Thornton, Management Consulting Partner, Richard Bycroft, and Director, Primo Danieletto, discuss automation in supply chains, triggers for reviewing an organisation’s current model and the ROI businesses can see from implementation. -

Client Alert A new trade landscape: insights for Australian businessesUS tariffs 2025: Impact on Australian exports, trade strategy & customs review insights.

Client Alert A new trade landscape: insights for Australian businessesUS tariffs 2025: Impact on Australian exports, trade strategy & customs review insights. -

Report Manufacturing benchmarks 2025: navigating complexity and building resilienceDiscover how Australian manufacturers are responding to slower growth, rising costs and tighter margins in our 2025 Manufacturing Benchmarks report, with insights on performance, reinvestment and capability-building.

Report Manufacturing benchmarks 2025: navigating complexity and building resilienceDiscover how Australian manufacturers are responding to slower growth, rising costs and tighter margins in our 2025 Manufacturing Benchmarks report, with insights on performance, reinvestment and capability-building.

-

Insight Navigating financial sustainability in a complex Not-for-Profit landscapeAgainst a backdrop of rising cost-of-living pressures and economic uncertainty, Not for Profits (NFPs) are facing increasingly complex challenges to maintain financial sustainability. With public expectations rising, funding pathways under strain, and operational costs climbing, many organisations are being forced to reassess how they operate. While the pressures are real, this also creates an opportunity to rethink collaboration, strengthen governance and build long-term resilience.

Insight Navigating financial sustainability in a complex Not-for-Profit landscapeAgainst a backdrop of rising cost-of-living pressures and economic uncertainty, Not for Profits (NFPs) are facing increasingly complex challenges to maintain financial sustainability. With public expectations rising, funding pathways under strain, and operational costs climbing, many organisations are being forced to reassess how they operate. While the pressures are real, this also creates an opportunity to rethink collaboration, strengthen governance and build long-term resilience. -

Insight Strengthening resilience for charities in a cost-of-living crisisAustralian charities are feeling the pinch of rising costs and increased demand as over 3.3m people live in poverty. From streamlining operations to diversifying funding streams and using technology like AI, leaders are finding ways to meet rising demand and stay resilient in today’s cost-of-living crisis.

Insight Strengthening resilience for charities in a cost-of-living crisisAustralian charities are feeling the pinch of rising costs and increased demand as over 3.3m people live in poverty. From streamlining operations to diversifying funding streams and using technology like AI, leaders are finding ways to meet rising demand and stay resilient in today’s cost-of-living crisis. -

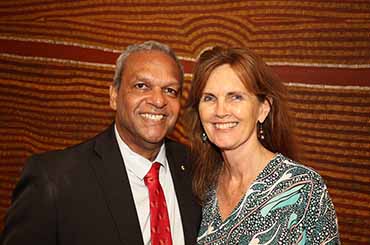

Podcast Yalari: empowering the next generation through educationYalari is a not-for-profit organisation offering secondary education scholarships to Australian schools for First Nations students. The organisation champions the value of education and nurtures an encouraging community for students to thrive in their studies.

Podcast Yalari: empowering the next generation through educationYalari is a not-for-profit organisation offering secondary education scholarships to Australian schools for First Nations students. The organisation champions the value of education and nurtures an encouraging community for students to thrive in their studies. -

Insight Federal Budget health and aged care initiatives announcedThe Health and Aged Care industry faces continued uncertainty, but following the Federal Budget announcements on 14 May, improvements are expected.

Insight Federal Budget health and aged care initiatives announcedThe Health and Aged Care industry faces continued uncertainty, but following the Federal Budget announcements on 14 May, improvements are expected.

-

Insight Profit allocation under PCG 2021/4 – are you ready?The ATO has made it clear that the professional services industry is in the spotlight as we head into 2026. With PCG 2021/4 now fully in effect as of 1 July 2024, the question is no longer if the ATO will review your arrangements, it is now a question of when. Is your firm ready?

Insight Profit allocation under PCG 2021/4 – are you ready?The ATO has made it clear that the professional services industry is in the spotlight as we head into 2026. With PCG 2021/4 now fully in effect as of 1 July 2024, the question is no longer if the ATO will review your arrangements, it is now a question of when. Is your firm ready? -

Insight Lessons from AusNet’s restructureThe Full Federal Court has handed down its decision in AusNet Services Limited v Commissioner of Taxation. AusNet argued that its 2015 restructure did not qualify for rollover relief under Division 615, despite that it earlier said it did. This case serves as a reminder that once a tax election is made, it is very difficult to unwind. Careful planning and forecasting are critical.

Insight Lessons from AusNet’s restructureThe Full Federal Court has handed down its decision in AusNet Services Limited v Commissioner of Taxation. AusNet argued that its 2015 restructure did not qualify for rollover relief under Division 615, despite that it earlier said it did. This case serves as a reminder that once a tax election is made, it is very difficult to unwind. Careful planning and forecasting are critical. -

Insight ATO final taxation ruling – TR 2025/2: Third Party Debt Test (TPDT)Australia’s new thin capitalisation rules significantly impact businesses with foreign ownership or offshore operations. If your business has debt deductions (such as interest deductions and borrowing costs) of more than A$2m, tax deductions could be denied under the primary ‘earnings tests’ (particularly if your EBITDA is low or negative due to early-stage losses, especially common in sectors like infrastructure and technology). To manage the above risk, the legislation offers an alternative test: the Third Party Debt Test (TPDT).

Insight ATO final taxation ruling – TR 2025/2: Third Party Debt Test (TPDT)Australia’s new thin capitalisation rules significantly impact businesses with foreign ownership or offshore operations. If your business has debt deductions (such as interest deductions and borrowing costs) of more than A$2m, tax deductions could be denied under the primary ‘earnings tests’ (particularly if your EBITDA is low or negative due to early-stage losses, especially common in sectors like infrastructure and technology). To manage the above risk, the legislation offers an alternative test: the Third Party Debt Test (TPDT). -

Insight How to practically achieve AML/CTF compliance for the Legal IndustryAustralia has commenced reforming its Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (AML/CTF) regime including the ‘Tranche 2’ reforms, which expand AML/CTF compliance to apply to additional professions including lawyers.

Insight How to practically achieve AML/CTF compliance for the Legal IndustryAustralia has commenced reforming its Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (AML/CTF) regime including the ‘Tranche 2’ reforms, which expand AML/CTF compliance to apply to additional professions including lawyers.

-

Insight Navigating cash flow and economic uncertainty in Real Estate & ConstructionRecent findings from the Family Business Report 2025 reveal that cash-flow management and economic uncertainty are the most pressing concerns for businesses in the construction and real estate sectors.

Insight Navigating cash flow and economic uncertainty in Real Estate & ConstructionRecent findings from the Family Business Report 2025 reveal that cash-flow management and economic uncertainty are the most pressing concerns for businesses in the construction and real estate sectors. -

Insights Rethinking investment and affordability in global real estate & construction marketsA global perspective on evolving real estate and construction markets, focusing on housing affordability, emerging asset classes, and sustainability. Gain insights from Grant Thornton’s experts across Australia and the UK help leaders navigate uncertainty and adapt investment strategies.

Insights Rethinking investment and affordability in global real estate & construction marketsA global perspective on evolving real estate and construction markets, focusing on housing affordability, emerging asset classes, and sustainability. Gain insights from Grant Thornton’s experts across Australia and the UK help leaders navigate uncertainty and adapt investment strategies. -

Client Alert Land banking under fire: VRLT expands to undeveloped sites from 2026From 2026, Victoria’s VRLT will apply to long-term undeveloped land in metro Melbourne, targeting land banking and encouraging residential development. The expansion follows 2025 reforms aimed at improving housing affordability and supply.

Client Alert Land banking under fire: VRLT expands to undeveloped sites from 2026From 2026, Victoria’s VRLT will apply to long-term undeveloped land in metro Melbourne, targeting land banking and encouraging residential development. The expansion follows 2025 reforms aimed at improving housing affordability and supply. -

Insight How to practically achieve AML/CTF compliance for the real estate industryAustralia has commenced reforming its Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (AML/CTF) regime including the ‘Tranche 2’ reforms, which expand AML/CTF compliance to apply to additional professions including real estate agents and conveyancers.

Insight How to practically achieve AML/CTF compliance for the real estate industryAustralia has commenced reforming its Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (AML/CTF) regime including the ‘Tranche 2’ reforms, which expand AML/CTF compliance to apply to additional professions including real estate agents and conveyancers.

-

Insight Unlocking the benefits of Australian Trusted Trader accreditationUnlock ATT accreditation to boost trade compliance, speed, and global market access.

Insight Unlocking the benefits of Australian Trusted Trader accreditationUnlock ATT accreditation to boost trade compliance, speed, and global market access. -

Podcast Finding the right fit in the evolving world of supply chain solutionsIn this episode of Beyond the Numbers with Grant Thornton, Management Consulting Partner, Richard Bycroft, and Director, Primo Danieletto, discuss automation in supply chains, triggers for reviewing an organisation’s current model and the ROI businesses can see from implementation.

Podcast Finding the right fit in the evolving world of supply chain solutionsIn this episode of Beyond the Numbers with Grant Thornton, Management Consulting Partner, Richard Bycroft, and Director, Primo Danieletto, discuss automation in supply chains, triggers for reviewing an organisation’s current model and the ROI businesses can see from implementation. -

Client Alert A new trade landscape: insights for Australian businessesUS tariffs 2025: Impact on Australian exports, trade strategy & customs review insights.

Client Alert A new trade landscape: insights for Australian businessesUS tariffs 2025: Impact on Australian exports, trade strategy & customs review insights. -

Report What’s driving Australian retail spending in today’s economy?Australian consumers are demanding more from retailers – better value, faster service, and consistently high quality. Discover what drives Australian retail and how to meet rising expectations.

Report What’s driving Australian retail spending in today’s economy?Australian consumers are demanding more from retailers – better value, faster service, and consistently high quality. Discover what drives Australian retail and how to meet rising expectations.

-

Insight What the Australian Clinical Labs privacy case means for cyber governance and M&A riskThe Federal Court’s $5.8M ACL decision signals a new era for privacy, cybersecurity, and governance in Australia. It reinforces that privacy and cyber obligations start Day 1 of any acquisition, governance failures will be scrutinised, and accountability cannot be outsourced. Boards must ensure robust oversight, deep cyber due diligence, and forensic incident response. With OAIC escalating regulatory enforcement, organisations face heightened legal, financial, and reputational risks.

Insight What the Australian Clinical Labs privacy case means for cyber governance and M&A riskThe Federal Court’s $5.8M ACL decision signals a new era for privacy, cybersecurity, and governance in Australia. It reinforces that privacy and cyber obligations start Day 1 of any acquisition, governance failures will be scrutinised, and accountability cannot be outsourced. Boards must ensure robust oversight, deep cyber due diligence, and forensic incident response. With OAIC escalating regulatory enforcement, organisations face heightened legal, financial, and reputational risks. -

Podcast From capital to sale: securing funding and exit strategies in the technology sectorIn this episode, National Head of Corporate Finance & M&A Partner Holly Stiles and National Head of Technology, Media & Telecommunications and Private Business Tax & Advisory Partner Jace Gawne-Buckland discuss the current technology landscape in Australia, evolving expectations of investors, and tangible steps tech leaders can take to strengthen their position for future raises or exits.

Podcast From capital to sale: securing funding and exit strategies in the technology sectorIn this episode, National Head of Corporate Finance & M&A Partner Holly Stiles and National Head of Technology, Media & Telecommunications and Private Business Tax & Advisory Partner Jace Gawne-Buckland discuss the current technology landscape in Australia, evolving expectations of investors, and tangible steps tech leaders can take to strengthen their position for future raises or exits. -

Report Unlocking value: navigating funding and exit strategies in technology businessesExplore strategies for scaling in Australia’s tech and SaaS sector in this report, covering capital raising, investor expectations, and long-term growth.

Report Unlocking value: navigating funding and exit strategies in technology businessesExplore strategies for scaling in Australia’s tech and SaaS sector in this report, covering capital raising, investor expectations, and long-term growth. -

Insight Tax planning essentials for successful M&A transactionsDiscover key tax planning steps for a smooth, tax-efficient M&A transaction.

Insight Tax planning essentials for successful M&A transactionsDiscover key tax planning steps for a smooth, tax-efficient M&A transaction.

-

Flexibility & benefits

The compelling client experience we’re passionate about creating at Grant Thornton can only be achieved through our people. We’ll encourage you to influence how, when and where you work, and take control of your time.

-

Your career development

At Grant Thornton, we strive to create a culture of continuous learning and growth. Throughout every stage of your career, you’ll to be encouraged and supported to seize opportunities and reach your full potential.

-

Diversity & inclusion

To be able to reach your remarkable, we understand that you need to feel connected and respected as your authentic self – so we listen and strive for deeper understanding of what belonging means.

-

In the community

We’re passionate about making a difference in our communities. Through our sustainability and community engagement initiatives, we aim to contribute to society by creating lasting benefits that empower others to thrive.

-

Graduate opportunities

As a new graduate, we aim to provide you more than just your ‘traditional’ graduate program; instead we kick start your career as an Associate and support you to turn theory into practice.

-

Vacation program

Our vacation experience program will give you the opportunity to begin your career well before you finish your degree.

-

The application process

Applying is simple! Find out more about each stage of the recruitment process here.

-

FAQs

Got questions about applying? Explore frequently asked questions about our early careers programs.

-

Our services lines

Learn about our services at Grant Thornton

-

Remarkable people

Our team members share their remarkable career journeys and experiences of working at Grant Thornton.

-

Working at Grant Thornton

At Grant Thornton we reach for remarkable and set the bar high to deliver a strikingly different experience for our people.

- Contact us

Australia is sitting on an untapped pot of money equivalent to the additional health investment the Australian Government has made since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s a cool $34 billion.

This lucrative untapped ‘shadow economy’ – defined as dishonest and criminal activities that take place outside the tax and regulatory systems – has been a long-standing issue for economies around the world. So long in fact, that it’s operated under numerous aliases, including ‘hidden’, ‘black’, ‘grey’, ‘informal’, ‘cash’ and ‘underground’.

At a time when Australia’s deficit is running close to $100 billion, this type of uncommitted funding would certainly come in handy, particularly as the Australian Government finalises its’ 2022-23 Federal Budget – the final one before the nation heads to the polls this year.

Getting a grip on a shapeless and faceless adversary

There’s a reason for the shadow economy’s name. It’s amorphous and evasive. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD ), economies around the world ‘are seeing a growth in labour market crime, increased cross-border frauds, increasingly sophisticated use of technology within the shadow economy and a potential threat to the tax base through opportunities offered by the rapid growth of the sharing and gig economies’.

In 2016-17, the Australian Government turned a floodlight on the issue establishing the Black Economy Taskforce - comprising 20 Commonwealth agencies - to ‘develop an innovative, forward-looking, multi-pronged policy response to combat the black economy’.

The taskforce’s final report made 80 recommendations to restrict the activities that fuel the shadow economy to start recouping the estimated $50 billion circulating within it. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has since estimated the tax gap to be closer to $33.5 billion in 2018-19. The Australian Government responded to the report with a package of whole-of-government measures covering everything from taxation reform to law enforcement, procurement and industrial relations.

Three years on, the ATO estimated it had clawed back $2.6 billion by the end of June 2021 through ‘new and enhanced enforcement strategies’. These have included removing tax deductibility of non-compliant payments; expanding the Taxable Payments Reporting System into new industries; increasing the integrity of the Commonwealth procurement process; and collecting tobacco duties and taxes at the Australian border.

It’s a start, probably a good one given the impact of COVID-19, but likely well shy of the expectations of a government that had been on a savings blitz to pay down billions of dollars in debt accumulated during the Global Financial Crisis.

The pandemic sends the economy deep into the red

Economic imperatives and government priorities have changed dramatically since the release of the Black Economy Taskforce report and the government’s response. Debt and spending have simultaneously exploded, both reaching record highs in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. With more pressing issues on the Australian Government’s policy agenda it’s unlikely that the shadow economy will attract headline investment in the coming Federal Budget.

The government has also been apprehensive on one of the taskforce’s priority recommendations – mandating the payment of salary and wages into bank accounts to stamp out ‘under the table’ cash payments to businesses and individuals.

The Australian Government may be less keen to tackle issues that have broad voter implications after its attempts to introduce an economy-wide cash payment limit of $10,000, as recommended by the taskforce, failed. The Senate blocked the proposed ‘cash ban’ law, which intended to make it harder for large anonymous cash payments to be used to avoid tax and reporting obligations. The draft bill attracted a range of criticism, including the harshness of the proposed financial penalties and its potential to restrict people’s civil liberties.

The cashless economy isn’t here, yet

Australians still like the security of cash, and monthly figures released by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) show that, following a lull, there has been an increase in the number and value of cash withdrawals during the last completed quarter (Dec 2021). However, long-term trend data shows our love for cash is waning. According to the RBA’s most recent triennial survey of consumer payments in 2019, Australians prefer using cards over cash: 67 percent versus 23 percent. In 2007, the results were reversed. Interestingly 22 percent of people surveyed in 2019 held no cash in their wallet, compared with eight percent in 2013. The next survey is due this year.

Cashless and contactless payments have certainly been embraced by businesses as part of national efforts to minimise the spread of COVID-19. In light of accelerated business uptake of cashless payment systems, could we see a revival of the ‘cash ban’ legislation, finetuned by new insights from COVID-19? This would appear unlikely – perhaps the economy has already voted with its COVID-averse feet.

With a Federal Election around the corner, the government’s stated focus is firmly on jobs growth, stimulating private sector investment, and building Australia’s sovereign capabilities to protect our national interests.

However, the shadow economy could again have its moment in the national spotlight. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has foreshadowed a potential audit to ‘assess the effectiveness of Treasury and other entities in implementing the 2018 government response to the Black Economy Taskforce's 2017 report’ in its 2021-22 work program.

Until that report is completed the shadow economy is likely to remain exactly where it is, in the shadows, out of sight and out of mind.