- CbC reporting obligations apply to MNEs with global income over AUD $1b, requiring submission of a Master File, Local File, and CbC Report to the ATO.

- The ATO has introduced a structured Local File format and narrowed exemptions, meaning more detailed reporting and stricter criteria for relief.

- Australia’s Public CbC regime requires certain large MNEs to publicly disclose jurisdictional tax and financial data, with first reports due 30 June 2026.

Tighter exemption criteria, enhanced reporting formats, and the introduction of Public Country-by-Country (“Public CbC”) reporting mean that multinational enterprises (“MNEs”) face not just compliance obligations, but real operational and reputational consequences. Companies that fail to upgrade systems, strengthen governance, and prepare for public disclosure risk regulatory penalties, scrutiny from stakeholders, and potential damage to their market credibility and strategic positioning.

Understanding the CbC reporting framework

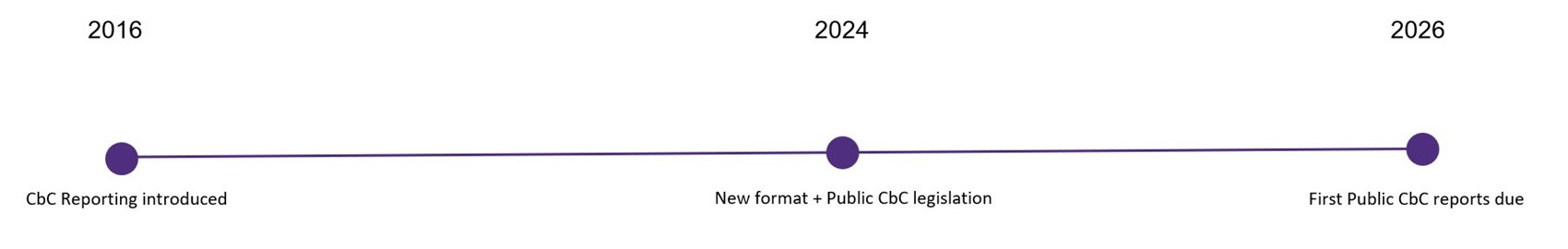

Since its introduction in 2016, Australia’s CbC reporting regime has become a cornerstone of the Australian Taxation Office’s (“ATO”) international tax compliance strategy. MNEs with consolidated global income of AUD 1 billion or more are required to lodge three key documents each year: the Local File, the Master File, and the CbC Report. Together, these filings give the ATO a detailed and holistic picture of a group’s global structure, value chain, and intercompany transactions, enabling it to assess transfer pricing risks and identify areas for further review.

Beyond simply meeting compliance requirements, the CbC framework has reshaped how MNEs approach tax governance. Many groups have enhanced their internal controls, standardised their global documentation, and invested in more robust data systems to ensure consistent and accurate reporting across jurisdictions.

ATO introduces structured Local File format

The ATO’s recent overhaul of the Local File format signals a move towards greater structure and standardisation in reporting. For income years commencing on or after 1 January 2024, affected entities must complete a revised Short Form Local File (“SFLF”), which replaces narrative, free-text responses with predefined fields and standardised data points.

This shift aims to improve comparability, enhance data integrity, and enable more efficient risk assessment by the ATO. However, it also increases the level of detail required, particularly in sensitive areas such as corporate restructures, financing arrangements, and strategic decision-making.

Exemptions from CbC reporting are now harder to obtain

Historically, certain entities were able to rely on exemptions from CbC reporting obligations. Recent changes have significantly tightened the criteria and process for securing such relief. Exemptions now require formal application, supported by robust evidence and detailed explanations as to why the reporting obligation should not apply. They are granted only in limited circumstances, reflecting the ATO’s increasing emphasis on transparency, consistency, and holding MNEs to the same high reporting standards. This change underscores the importance for businesses to assess eligibility early and ensure they have comprehensive documentation before seeking relief.

Public CbC reporting regime takes effect

The introduction of the Public CbC reporting legislation in July 2024 marks a major shift in Australia’s tax transparency framework. Certain large MNEs with significant Australian operations will now be required to publicly disclose tax and financial data on a jurisdictional basis. The first public reports will be due by 30 June 2026 for entities with a 30 June 2025 year-end.

While the regime aligns broadly with global tax transparency initiatives, Australia’s version includes distinctive features such as de minimis thresholds and jurisdiction-specific disclosure requirements. For affected businesses, the move to public disclosure raises both compliance and reputational considerations, requiring proactive communication strategies to manage stakeholder expectations.

Looking ahead

As the regulatory landscape continues to shift, CbC and Public CbC reporting are no longer just compliance exercises – they’re strategic tools for demonstrating transparency, managing reputational risk, and aligning with global best practices. Businesses that take a proactive approach to these obligations will be better positioned to respond to scrutiny, engage confidently with regulators, and build trust with stakeholders.

If you’re looking to navigate these changes and unlock greater value from your tax governance and reporting processes, our team offers practical insights, tailored support, and a clear focus on outcomes. Please get in touch with one of our experts to explore how we can help you prepare for what’s next.